Problem: NOx and VOCs

Dangerous air pollutants

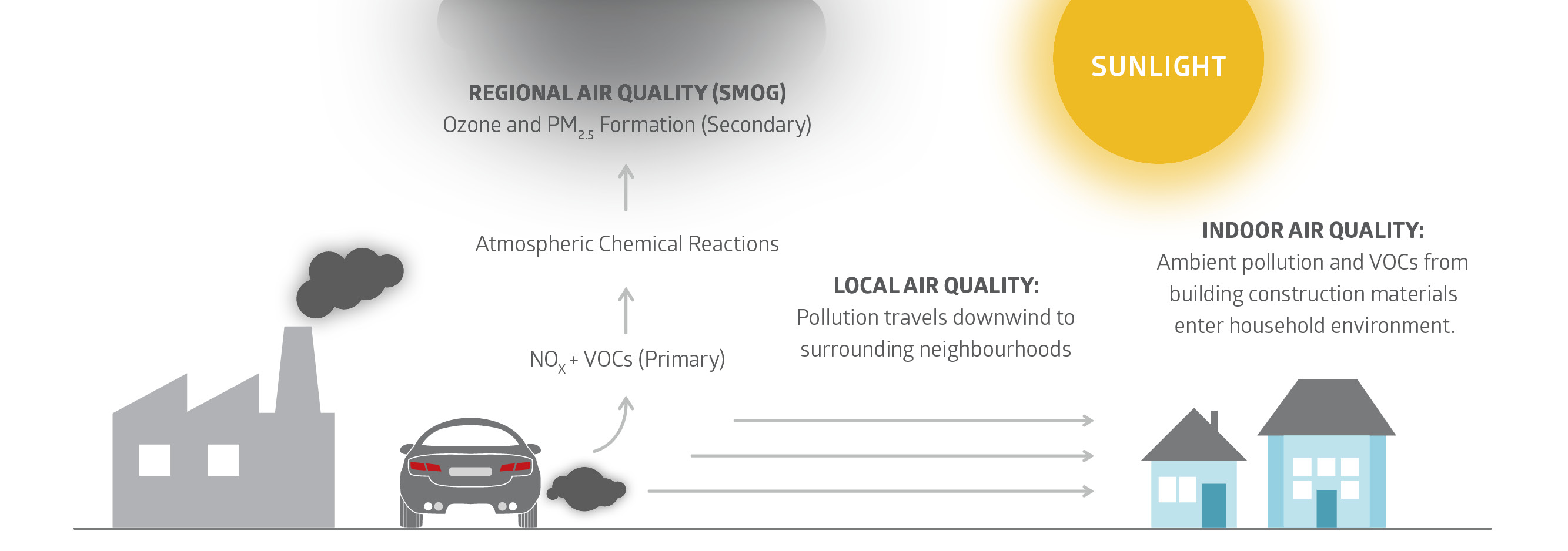

We all need to breathe. But much of the air we inhale contains nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) — pollutants that can cause everything from asthma to cancer. And that’s a problem: indoors, locally and regionally.

Regional Air Quality

On hot, sunny days, local air pollution can turn into an even larger problem, when the NOx and VOCs from cars and smokestacks undergoes a series of chemical reactions that generate smog.

The result can blanket the entire region, leading to thousands of premature deaths, overloading emergency rooms and making it dangerous to exercise outdoors.

Regional Air Quality

As of 2013, almost 90 per cent of the world’s population lives in areas where outdoor air pollution exceeds the World Health Organization’s Air Quality Guideline.1

The effects are deadly. In 2016 alone, ambient air pollution killed 4.2 million people and affected the health of many more.2

A cocktail of pollutants

Ambient air pollution contains a cocktail of substances, including nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Those are dangerous in their own right, creating problems that range from coughing and wheezing to central nervous system problems and cancer.3,4

But the damage doesn’t stop there. When exposed to sunlight, these pollutants can create ground-level ozone: a significant contributor to asthma, respiratory diseases and other breathing problems.5

Today, more people than ever are feeling the impact. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the number of premature deaths caused by ambient ozone pollution increased by nearly 30 per cent between 2000 and 2015.6

Devastating smog

Hot, sunny days can also trigger photochemical reactions that transform NOX and VOCs into smog. Smog can blanket an entire region in pollution or get blown hundreds of kilometres, creating health impacts far from its original source. In fact, studies have shown that air pollution from Asia can travel across the Pacific Ocean, all the way to North America.7

Those health impacts range from minor to lethal. Smog irritates eyes, noses and throats. It aggravates heart and lung problems. Meanwhile, pregnant women exposed to ambient air pollution are more likely to have babies with low birth weights and other complications.8

Smoggy days lead to thousands of premature deaths, overload emergency rooms and make it dangerous for even healthy people to exercise outdoors. In London, nearly 9,500 people die prematurely each year because of air pollution.9 In many other countries, the toll is even higher. In Beijing, for example, breathing the smog-filled air creates the same health risks as smoking 40 cigarettes a day.10

A costly problem

Financially, air pollution costs the global economy hundreds of billions of dollars in lost labour income each year.11 Meanwhile, an OECD report estimates that global healthcare costs related to air pollution could increase eight-fold by 2060.12

1http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/781521473177013155/pdf/108141-REVISED-Cost-of-PollutionWebCORRECTEDfile.pdf

2WHO. 2018. Ambient (Outdoor) Air Quality and Health. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health

3https://www.epa.gov/no2-pollution/basic-information-about-no2#Effects

4https://www.lung.org/our-initiatives/healthy-air/indoor/indoor-air-pollutants/volatile-organic-compounds.html

5https://www.epa.gov/ground-level-ozone-pollution/health-effects-ozone-pollution

6Roy, R. and N. Braathen (2017), “The Rising Cost of Ambient Air Pollution thus far in the 21st Century: Results from the BRIICS and the OECD Countries”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 124, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/d1b2b844-en.pdf?expires=1552421681&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=AB0DD45DFA0AB3CFF217AD1B136E2606

7Toa, Z., Yu, H., Chin, M. 2015. Impact of transpacific aerosol on air quality over the United States: A perspective from Aerosol-cloud-radiation interactions. Atmospheric Environment 125, November 2015.

8Smith, R.B., Fecht, D., Gulliver, J., Beevers, S.D., Dajnak, D., Blangiardo, Marta et al. 2017. Impact of London’s road traffic air and noise pollution on birth weight: retrospective population based cohort study BMJ 359: j5299. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5299

9https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jul/15/nearly-9500-people-die-each-year-in-london-because-of-air-pollution-study

10Rohde, R.A., Muller, R.A. 2015. Air pollution in China: Mapping of Concentrations and Sources. PLoS One. 10(8): e0135749. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135749

11 http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/781521473177013155/pdf/108141-REVISED-Cost-of-PollutionWebCORRECTEDfile.pdf

12 OECD. 2016. The Economic Consequences of Outdoor Air Pollution. http://www.oecd.org/environment/indicators-modelling-outlooks/the-economic-consequences-of-outdoor-air-pollution-9789264257474-en.htm

Local Air Quality

The World Health Organization has declared outdoor air pollution a public health emergency, responsible for 4.2 million deaths in 2016.

Industry and traffic are a big part of the problem, generating NOx, VOCs, particulates, sulphur dioxide and more. And people living or working near major roads, highways or industrial emitters suffer the greatest health consequences.

Traffic-related Air Pollution

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared outdoor air pollution a public health emergency,1 responsible for 4.2 million deaths in 2016.2 Traffic is a big part of the problem.

Although most countries have put emissions standards in place, increasing urbanization has led to more congestion3 — and thus the kind of stop-and-go traffic that produces more pollution.

Meanwhile, there are more vehicles on the road than ever,4 each one generating nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), particulates, sulphur dioxide and more. In China, for example, the number of vehicles doubled between 2009 and 2011,5 making traffic the single largest source of urban air pollution.6

Hard to escape

Even in high-income European countries, more than three-quarters of residents live in areas where the level of outdoor air pollution exceeds WHO guidelines.7 According to OECD estimates, about half of that is due to road transportation.8

Nor do concentrations need to be high to create health problems. In two recent studies, Harvard researchers found air pollution levels below EPA thresholds still increased the risk of premature death in Americans 65 and older.9

According to the Health Effects Institute, people who live close to high-traffic roadways have the highest health risks. In North America, nearly 45 per cent of residents in big urban centres live within 500 metres of a highway or major road — the zone most affected by vehicle emissions.10

A public health emergency

Traffic-related air pollution can lead to short-term and long-term health problems: asthma, respiratory infections, pulmonary disease, lung cancer, heart disease and stroke.11 A growing body of evidence suggests that it also impairs brain function, affecting school performance in children12 and increasing the risk of dementia in older people.13, 14 Meanwhile, pregnant women exposed to air pollution are more likely to have low-birth-weight babies.15

More than 58,000 premature deaths in the U.S. can be linked directly to poor air quality from the transportation industry.16 And the price tag is high: in OECD countries alone, the health impacts of traffic total an estimated US$85 billion.17

1WHO. 2016. Ambient Air Pollution: A Global Assessment of Exposure and Burden of Disease. Geneva: World Health Organization.

2 WHO. 2018. Ambient (Outdoor) Air Quality and Health. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health

3 TomTom. 2017. TomTom Traffic Index 2017: Mexico City Retains Crown of ‘Most Traffic Congested City in World’ https://library.tomtom.com/web/3ad15caf20061163/tomtom-traffic-index-2017/

4Petit, S. 2017. World vehicle population rose 4.6% in 2015. WardsAuto. Oct 17, 2017. http://subscribers.wardsintelligence.com/analysis/world-vehicle-population-rose-46-2016

5OECD. 2014. The Cost of Air Pollution: Health Impacts of Road Transport. Pairs: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264210448-en https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264210448-en

6Zhong, N., Cao, J., Wang, Y. 2015. Traffic congestion, ambient air pollution, and health: evidence from driving restrictions in Beijing. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 4(3): 821:856. https://doi.org/10.1086/692115

7World Health Organization. 2018. Exposure to ambient pollution from particulate matter for 2016.

8OECD. 2014. The Cost of Air Pollution: Health Impacts of Road Transport. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264210448-en

9Di, Q., Wang, Y., Zanobetti, A., Wang, Y., Koutrakis, P., Choirat, C., Dominici, F., Schwartz, J.D. 2017. Air pollution and mortality in the entire Medicare population. N. Engl. J. Med. 376: 2513–2522. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1702747; Qian, D., Lingzhen, D., Wang, Y., Zanobetti, A., Choirat, C., Schwartz, J.D., Dominici, F. 2017. Association of short-term exposure to air pollution with mortality in older adults. JAMA 318(24): 2446–2456. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.17923

10Health Effects Institute. 2010. Traffic-Related Air Pollution: A Critical Review of the Literature on Emissions, Exposure, and Health Effects. Boston: Health Effects Institute.

11Global Road Safety Facility, The World Bank; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 2014. Transport for Health: The Global Burden of Disease from Motorized Road Transport. Seattle: WA: IHME; Washington, DC: The World Bank.

12Kweon, B-S., Mohai, P., Lee, S., Sametshaw, A.M. 2016. Proximity of public schools to major highways and industrial facilities, and students’ school performance and health hazards. Environ. Plan B Urban Anal. City Sci. 45(2): 312–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813516673060

13Zhang X, Chen X, Zhang X. 2018. The impact of exposure to air pollution on cognitive performance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115(37): 9193–9197. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1809474115

14Chen, H., Kwong, J.C., Copes, R., Tu, K., Villeneuve, P.J., van Donkelaar, A., Hystad, P., Martin, R.V., Murray, B.J., Jessiman, B., Wilton, A.S., Kopp, A., Burnett, R.T. 2017. Living near major roads and the incidence of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Lancet 389 (10070): 718–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32399-6

15Smith, R.B., Fecht, D., Gulliver, J., Beevers, S.D., Dajnak, D., Blangiardo, Marta et al. 2017. Impact of London’s road traffic air and noise pollution on birth weight: retrospective population based cohort study. BMJ 359: j5299. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5299

16Caiazzo, F., Ashok, A., Waitz, I.A., Yim, S.H.L., Barrett, S.R.H. 2013. Air pollution and early deaths in the United States. Part I: Quantifying the impact of major sectors in 2005. Atmos Environ. 79: 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.05.081

Indoor Air Quality

Typical North Americans spend more than 90 per cent of their time inside buildings, where the air quality is often worse than outdoors.

Traffic and industrial pollution can sneak inside through doors, windows and HVAC systems. Meanwhile, paints, carpets and construction materials give off VOCs, including formaldehyde.

Indoor Air Quality

Although the concentrations of many pollutants are lower indoors, those levels can still be high enough to affect health. Meanwhile, concentrations of some pollutants are actually higher indoors than out.

Infiltration of outdoor pollution

Air pollutants make their way into homes and offices through open windows, doors and ventilation systems. They also infiltrate through cracks and leaks in the building envelope2. As a result, buildings located near busy roads and industrial areas can have dangerous elevated levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), particulates and more.

For example, schools located near petrochemical plants in Spain had higher levels of benzene in their classrooms3, while an Australian study found increased levels of NO2 and toluene in homes within 50 metres of major roads4.

This kind of industrial and traffic-related pollution can have serious consequences — increasing the risk of everything from low birth weight babies5 to asthma6, poor school performance7, cancer8 and dementia9.

Uniquely indoor dangers

However, outdoor sources are just one part of the problem. A number of dangerous pollutants actually originate indoors: from the operation of printers and photocopiers; off-gassing from new furniture and carpets; the use of paints, adhesives, cleaning chemicals and aerosol sprays; and activities such as cooking and smoking.

For example, research in the Chinese city of Hangzhou revealed VOC concentrations inside homes were higher than those recorded outside. The levels were highest in new buildings, due largely to solvents, paints and home decor10. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, health risks created by VOCs include headaches, nausea, fatigue, liver and kidney damage and cancer11.

Costly consequences

Because we spend so much time indoors, the health impacts can be serious — and even deadly. They hit children and the elderly particularly hard.

The latest statistics from the World Health Organization reveal 117,200 premature deaths in Europe were caused by indoor air pollution in 2012, while 3.9 million years were lost as a result of disease and premature death12. A recent French study estimated that healthcare expenses, loss of productivity and premature death from indoor air pollution cost the country €19 billion in 200413.

1Leech, J.A., Nelson, W.C., Burnett, R.T., Aaron, S., Raizenne, M.E. 2002. It’s about time: A comparison of Canadian and American time-activity patterns. J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 12: 427–432. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jea.7500244

2Chen, C., Zhao, B. 2011. Review of relationship between indoor and outdoor particles: I/O ratio, infiltration factor and penetration factor. Atmos. Environ. 45(2): 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.09.048

3Villanueva, F., Tapia, A., Lara, S., Amo-Salas, M. 2018. Indoor and outdoor air concentrations of volatile organic compounds and NO2 in schools of urban, industrial and rural areas in Central-Southern Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 622–623: 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.274

4Lawson, S.J., Galbally, I.E., Powell, J.C., Keywood, M.D., Molloy, S.B., Cheng, M., Selleck, P.W. 2011. The effect of proximity to major roads on indoor air quality in typical Australian dwellings. Atmos. Environ. 45(13): 2252–2259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.01.024

5Gong, X., Lin, Y., Bell, M.L., Zhan, F.B. 2018. Associations between maternal residential proximity to air emissions from industrial facilities and low birth weight in Texas, USA. Environ. Int. 120: 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.07.045

6Bowatte, G., Erbas, B., Lodge, C.J., Knibbs, L.D., Gurrin, L.C., Marks, G.B., Thomas, P.S., Johns, D.P., Giles, G.G., Hui, J., Dennekamp, M., Perret, J.L., Abramson, M.J., Walters, E.H., Matheson, M.C., Dharmage, S.C. 2017. Traffic-related air pollution exposure over a 5-year period is associated with increased risk of asthma and poor lung function in middle age. European Respiratory Journal 50: 1602357. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02357-2016; Gauderman, W.J., Avol, E., Lurmann, F., Kuenzli, N., Gilliland, F., Peters, J., McConnell, R. 2005. Childhood asthma and exposure to traffic and nitrogen dioxide. Epidemiology: 16(6): 737–743. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ede.0000181308.51440.75

7Kweon, B-S., Mohai, P., Lee, S., Sametshaw, A.M. 2016. Proximity of public schools to major highways and industrial facilities, and students’ school performance and health hazards. Environ. Plan B Urban Anal. City Sci. 45(2): 312–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813516673060

8Bidoli, E., Pappagallo, M., Birri, S., Frova, L., Zanier, L., Serraino, D. 2016. Residential proximity to major roadways and lung cancer mortality. Italy, 1990–2010: an observational study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13(2): 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13020191

9Chen, H., Kwong, J.C., Copes, R., Tu, K., Villeneuve, P.J., van Donkelaar, A., Hystad, P., Martin, R.V., Murray, B.J., Jessiman, B., Wilton, A.S., Kopp, A., Burnett, R.T. 2017. Living near major roads and the incidence of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Lancet: 389 (10070): 718–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32399-6

10Ohura, T., Amagai, T., Shen, X., Li, S., Zhang, P., Zhu, L. 2009. Comparative study on indoor air quality in Japan and China: Characteristics of residential indoor and outdoor VOCs. Atmos. Environ. 43(40): 6352–6359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.09.022

11https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/volatile-organic-compounds-impact-indoor-air-quality

12http://www.euro.who.int/en/media-centre/sections/press-releases/2015/04/air-pollution-costs-european-economies-us$-1.6-trillion-a-year-in-diseases-and-deaths,-new-who-study-says

13Boulanger, G., Bayeux, T., Mandin, C., Kirchner, S., Vergriette, B., Pernelet-Joly, V., Kopp, P. 2017. Socio-economic costs of indoor air pollution: A tentative estimation for some pollutants of health interest in France.

Environment International 104: 14–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.03.025